This was written as the final paper for my Environment & Society course Spring 2020

Environmental Ethic

I hold an ecocentric environmental ethic. I believe that nature has inherent value, and that all species are a part of nature. As such, I believe that access to natural spaces is the right of all animals, including humans. Not all humans have this access equally and this inequality has been discussed as an issue of environmental justice.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice frequently considers how pollution and the effects of climate change have more adverse consequences for marginalized people. It can also refer to how those same people tend to have less access to natural or green spaces than others have. Even when people in these groups have physical access to natural spaces, they are less likely to visit them (NPS, 2006). There are a number of theories about why this might be, one of which is that “naturalists” are often depicted as white people, usually with expensive gear and the ability to travel to “wild” places (Newsome, 2020). This depiction of naturalists raises the question Who tells the story about nature?

In addition to whiteness, nature is also frequently associated with science, which is, in turn, associated with more whiteness and with Western-style academia. This story of nature can be off-putting to broader audiences, limiting their willingness to spend time in natural spaces. This story can cause people who don’t see themselves in it to feel disconnected from nature, and not feel that nature is a place for them. Research in environmental education holds that a sense of place is a key component for creating excitement about and concern for nature. The lack of connection to place makes it difficult to engage broader audiences with their natural world.

Sense of Place

The idea of a sense of place has been defined numerous ways in the literature (Cross, 2001; Halliwell, 2019). Themes that appear throughout the definitions include “bonding, connecting, relating, and associating through various means” (Halliwell, 2019). A person who lacks these feelings for a place may have negative associations with the place, which can happen when their environment is polluted and cared for less by larger bodies (cities, states, or country). Not seeing yourself in the place can also disconnect a person from their environment. The story needs to change to show a wider variety of people in the place.

Potential of Community Science

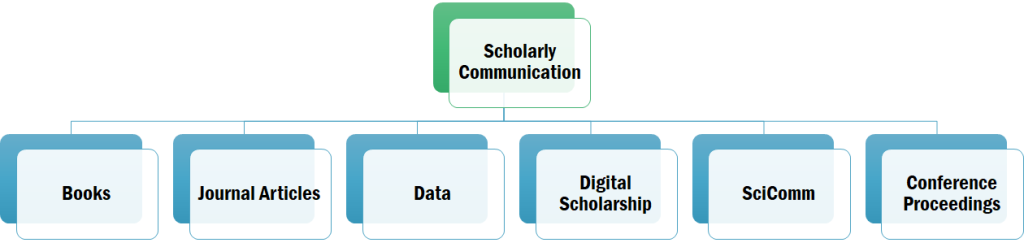

There are many different approaches to environmental education that take place in a variety of locations, with a variety of methods and activities. One type of activity that sometimes falls within environmental education is community science, also known as citizen science. Community science employs volunteers to collect data and partake in other steps of the research process. Community science is helpful for scientists, particularly in the natural sciences, because it allows them to collect much more data than they could on their own. Some research has also been done to examine the benefits that volunteers gain from participating in community science projects (Peter, et al, 2019). This research is encouraging, although there is very little of it. Peter et al, in their 2019 review of the literature on nature-based community science projects, found only 14 papers studying the benefits experienced by community science volunteers from through 2017. Almost all of these papers found that participants in community science projects experienced positive benefits from their work, including gains in knowledge about their environment or study species, positive attitudes changes towards nature or their study species, and an increased sense of place.

Haywood (2014, 2019) and Haywood et al (2016) have looked most frequently and elaborately into the effect that participation in community science can have on volunteers’ sense of place. He has found increases in connection to place in volunteers’ work on a project monitoring coastal birds. He hypothesizes that the repeated visits to the locations where monitoring took place helped build this sense of place that volunteers reported. Halliwell (2019) found similar results for volunteers in community science programs in two National Parks. These results show real potential for community science to help build a sense of place for participants. Some research shows that building a sense of place is usually only done over long periods of time (Raymond et al, 2017) and community science may be a way to get this result more quickly.

Limitations of Community Science

While community science looks to be an exciting way to allow people to write themselves into the story of nature, there are still barriers that leave behind the same groups of people. Demographic information is not often collected about who participates in community science, but it’s easy to imagine that participants have the privilege of time to volunteer, and likely already identify as interested in nature and science to some degree. Commonly referred to as “citizen science,” the activities can also be off-putting to non-citizens, and even “community science” can fail to attract people who don’t feel they are part of “the community.” Many people in this country believe they aren’t adept at science and may be disinterested in any science activities. The literature does little to address or even identify these problems of participation in community science.

One area that is thinking more diversely about who community science helps is environmental justice. Community science is a useful method to expose inequalities in the environment, such as air and water quality and access to green space. Dhillon (2017) acknowledges that lay scientists (volunteers) and professional scientists may fall into opposition with each other during community science projects. She notes that community science brings together these different knowledge bases and calls for these knowledge bases to instead interrogate each other to strengthen the knowledge they create. Community science projects with goals related to environmental justice issues are more likely to include groups that are generally not represented in the story of nature. These projects give participants a sense of ownership over their environments (Dhillon, 2017; Jiao et al, 2016; Rickenbacker et al, 2016), which contributes to a sense of place.

Recommendations

It’s difficult to determine the best recommendations to increase diversity in community science participation, or to increase the cultivation of a sense of place. The literature about outcomes for community science volunteers is sparse and there is no standard framework for evaluating outcomes. Peter et al (2019) make the recommendation that nature-based community science projects should be designed along with social scientists to make use of established educational frameworks to evaluate outcomes related to knowledge gains and other measures of success for participants. Peter et al also recommend that research be done on multiple community science projects, rather than single case studies that are quite common, and more longitudinal studies about the long-term effects of participation on volunteers. These recommendations would all improve our understanding of how volunteers benefit from community science and what factors produce which benefits. Haywood (2014) also recommends more research to see what factors lead to an increased sense of place.

The community science projects with the most benefits for volunteers are those that are co-created by the community and scientists. In addition to working with social scientists, natural scientists creating community science projects should have volunteers from the community help establish research questions and methods. These tactics help increase trust in science and feelings of accomplishment by volunteers (Peter et al, 2019). This process could also increase the volunteers’ sense of place by encouraging them to think about their place in the community and how they relate to it.

Conclusion

Nature-based community science projects have potential to rewrite the story of nature to include more people, but the project must make concerted efforts to get members of underrepresented groups to participate and engage with the project. Professional scientists must connect to the community they’re studying and working with and respect the knowledge people there have about their community and environment. If a scientist pushes their own narrative about the environment onto the community, they will squash any hope of rewriting the story of nature.

References

Cross, J.E. (2001). What is sense of place? 12th Headwaters Conference, Western State College, November 2-4, 2001.

Dhillon, C. M. (2017). Using citizen science in environmental justice: Participation and decision-making in a southern california waste facility siting conflict. Local Environment, 22(12), 1479-1496. doi:10.1080/13549839.2017.1360263

Halliwell, P.H. (2019). National Park citizen science participation:Exploring place attachment and stewardship. (Publication number 134613880267). [Doctoral dissertation, Prescott College]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Haywood, B. (2019). Citizen science as a catalyst for place meaning and attachment. Environment, Space, Place, 11(1), 126-151. doi:10.5749/envispacplac.11.1.0126

Haywood, B.K. (2014). A “sense of place” in public participation in scientific research. Science Education, 98(1), 64-83. doi:10.1002/sce.21087

Haywood, B. K., Parrish, J. K., & Dolliver, J. (2016). Place-based and data-rich citizen science as a precursor for conservation action. Conservation Biology, 30(3), 476-486. doi:10.1111/cobi.12702

Jiao, Y., Bower, J. K., Im, W., Basta, N., Obrycki, J., Al-Hamdan, M. Z., Wilder, A., Bollinger, C.E., Zhang, T., Hatten, L.S., Hatten, J., & Hood, D. B. (2015;2016;). Application of citizen science risk communication tools in a vulnerable urban community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), ijerph13010011. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010011

Newsome, C. (@hood_naturalist). (2020, May 29). MAJOR ANNOUNCEMENT!!!!! We at @BlackAFinSTEM are starting the inagural #BlackBirdersWeek to celebrate Black Birders and nature explorers, beginning 5/31!!!!! Follow the whole group of us here: https://twitter.com/i/lists/1266155155743027202 Take a look at the thread for the schedule of events! [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/hood_naturalist/status/1266387163727486977

Peter, M., Diekötter, T., & Kremer, K. (2019). Participant outcomes of biodiversity citizen science projects: A systematic literature review. Sustainability,11(2780). doi:10.3390/su11102780

Raymond, C. M., Kyttä, M., & Stedman, R. (2017). Sense of place, fast and slow: The potential contributions of affordance theory to sense of place. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1674. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01674

Rickenbacker, H., Brown, F., & Bilec, M. (2019). Creating environmental consciousness in underserved communities: Implementation and outcomes of community-based environmental justice and air pollution research. Sustainable Cities and Society, 47, 101473. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101473

U.S. Department of the Interior/Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs. (2006). NPS Visitation Trends. https://www.doi.gov/ocl/nps-visitation-trends